Nothing gets the market pulse racing quite like the US Treasury 10-year note yield popping above 3 per cent for the first time in four years.

A fiscal shot for the economy via tax reform, a tightening jobs market combined with a substantial increase in Federal borrowing means it’s hardly surprising that Treasury yields are rising. Stronger expectations for growth and inflation warrant recognition via a revised policy statement from Federal Reserve officials when they conclude their latest meeting on Wednesday.

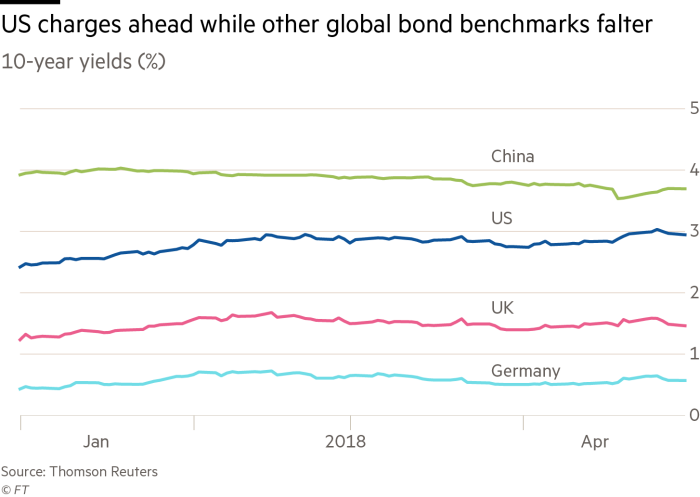

But while US yields are set to rise further, a different story has quietly emerged among other global bond benchmarks. Eurozone and UK 10-year benchmarks remain adrift of peaks reached in February.

More troubling for the global economy and investment portfolios is how bond yields in China have notably dropped in recent months, suggesting an economy feeling the pinch from a tighter grip on liquidity by authorities.

And entering May, the comforting backdrop of a sustained and synchronised cycle of global growth has taken a knock. Central banks in Sweden, Canada, the UK and Australia have recently tempered talking more hawkishly about the direction of future policy.

With global data outside of the US arriving below expectations, some such as Chris Watling at Longview Economics argue “we had synchronised growth and now the global industrial cycle is rolling over”.

If recent economic weakness is not a temporary pause then many investors face a tough summer adjusting to a new divergence between the US and global rivals. Investor expectations of a weak dollar, a firming recovery in the eurozone and sustained growth across emerging markets has long held sway across portfolios.

The risk of a pronounced portfolio shakeout looms as the dollar continues rising and as doubts grow over the prospects for industrial and cyclical companies, excluding energy, and red flags flutter more briskly across emerging markets.

JPMorgan’s emerging markets currency index dropped 3.2 per cent in April, its worst monthly loss since November 2016. Beyond a bruising month for the Russian rouble courtesy of further sanctions from the US, currencies for the likes of Brazil, Mexico and South Africa have also suffered. And in the case of Turkey and Argentina, central banks have been forced to raise interest rates to support their currencies.

The likely poster child for EM bullishness for this cycle was the massive demand for Argentina’s 100-year bond sale in 2017. The price for that paper has fallen below 90 cents.

A less certain global backdrop will hardly deter the Fed from its present course of steady policy tightening. Indeed, there is a risk that they push a little harder, particularly should fiscal stimulus and higher oil prices push inflation measures higher.

At least two and more likely three rate increases beckon this year, while the reduction in the size of the central bank’s balance sheet will also gather pace. As the Fed’s quantitative tightening intensifies, the reduction in financial system liquidity alongside a stronger dollar will tighten financial conditions.

That will hardly help a global economy that appears to have peaked, let alone alleviate badly positioned portfolios. At some point and perhaps sooner than many think, the question of the Fed reaching for the pause button will gain traction.

“This is a world that has too much debt, and against such a structurally deflationary backdrop it can’t take too much tightening,” says Mr Watling, who adds “as we get to 2019, we think the Fed will pause as there are large risks”.

Indeed, the International Monetary Fund recently sounded the alarm over a global debt of $164tn, of which half is held by the US, Japan and China, and which has eclipsed the peak of the financial crisis a decade ago.

Years of aggressive monetary policy and quantitative easing has only encouraged more debt, with US companies playing a starring role. A greater concern is that rock-bottom interest rates in major countries has spurred a credit boom across emerging markets. Non-performing loans in China and Europe are high, posing a big risk to financial stability.

“The endgame is more fragile public and private balance sheets, which are vulnerable to a tightening in financial conditions,” notes Alberto Gallo of Algebris Investments. “Our base case scenario is now one of a hawkish Federal Reserve hurting the recovery through a global tightening of financial conditions, before other central banks have time to normalise their policy.”

michael.mackenzie@ft.com