The return of inflation and how central banks respond if it does are key issues

Markets have swerved away from some deep-seated patterns this week: the 10-year Treasury yield, which sets the cost of money for the world has risen its most since election week; stocks have had their worst week in two years; and in the alternate universe where cryptocurrencies trade, bitcoin has fallen 60 per cent from its pre-Christmas peak.

None of these developments can yet be called a car crash or a train wreck. (Not even bitcoin, which has logged 90 per cent falls and rebounded in the past.) But there is something to the driving analogy. We are at a treacherous junction. If any of a number of different actors misjudges, or tries to do things too fast, then there certainly is a risk of a crash. To navigate it, we need to understand where we started.

The world has had very low interest rates ever since the 2008 financial crisis. Financial conditions remain historically loose. But those rates look ever harder to justify. After all, the stock market has been rallying in response to impressive numbers suggesting that economic growth is back; both retail and institutional investors have their animal spirits back, as money flowed into stock funds last month in a way not yet seen this century; and corporate earnings are good. According to Citi, brokers are now braced for global earnings growth of 14 per cent in 2018, up from 11 per cent at the beginning of the year. Understandably, the Federal Reserve has raised short-term rates by a percentage point since December 2016, and is virtually certain to raise rates again next month.

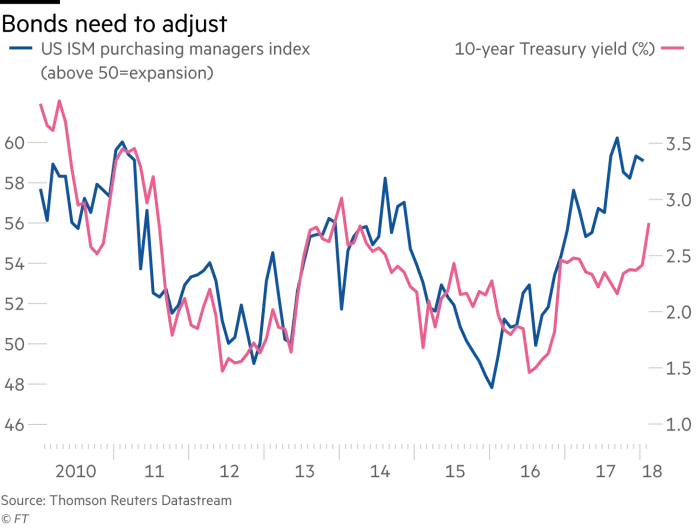

None of these things is consistent with a bond market that offered the chance to borrow for 10 years at 2.4 per cent barely a month ago. Bonds are complex, but the issues boil down to this: if the economy is as good as other markets say, Treasury yields have to be higher. The latest data point is Friday’s release of US wage data, showing average hourly earnings are rising at an annualised rate of 2.9 per cent — the highest this decade. This is great news for US workers struggling with stagnant living standards, but means that markets must adjust. Following the data, the 10-year yield surged up to again, to touch 2.85 per cent — which is still not that high in historical terms.

Meanwhile stocks had enjoyed a “melt-up”, breaking above the upward trend that has lasted for several years. That can be explained by the excitement generated by the tax cut at the end of last year, coupled with new flows from asset allocators at the beginning of the year. Some correction from this excess is both likely and healthy.

So far, then, stocks and bonds are navigating a sensible path away from a very strange place. What happens next depends on the bond market.

When Treasury yields move upwards they tend to do so in a hurry, especially after passing points of resistance. Once the 10-year yield passed 2.66 per cent on Monday, the long-term declining trend in yields seemed to be broken — allowing this week’s sharp jump. The next point of resistance is 3 per cent. Besides being a round number, it would also bring the yield more than two deviations above the downward trend (really suggesting that trend was over), and it would top the recent peak set in 2013. If the yield quickly moves above 3 per cent, a lot of calculations go awry: about 12 per cent of US companies are “zombies” by the calculations of London’s Longview Economics, meaning that their earnings before interest and tax do not cover their interest expense. A quick rise in rates could ruin them. Higher US rates would also pull money out of emerging markets. Will this happen? Bonds are oversold and could easily rebound. Further rises need continued evidence of inflation. But the US has just stoked its deficit with a tax cut. It must borrow a lot this year. That will push up the price (or yield) that Uncle Sam has to pay. Does a 3 per cent plus yield bring stocks down? Possibly not. Sharmin Mossavar-Rahmani of Goldman Sachs suggests yields need to exceed nominal economic growth — about 4 per cent — before creating difficulties, and that most S&P 500 corporate debt is fixed. There may be more time for everyone to adjust. And ultimately, as ever, we return to central banks. Many argue, from the experience of the last 20 years, that they would cave as soon as asset prices began to sag, and cut rates. But US financial conditions remain historically loose, according to the Chicago Fed. And the Fed is mandated to limit inflation. If (a critical if) inflationary pressure has returned, it is far harder for the Fed to bail out the stock market. After the decision not to invite back Janet Yellen, the Fed is under the new leadership of Jay Powell. He needs to establish his credibility, and the market wants to test him. So these are two critical questions in determining whether a difficult adjustment turns into a crash. First, does inflation really return? And second, how do central banks respond if it does? Keep focused on those questions as markets make their perilous manoeuvre. john.authers@ft.com