How much protection do people deserve when they venture into markets? After the longest period on record without a stock market sell-off — or “correction” — capital markets reminded this week that setting prices is painful.

It involves the interaction of greed and fear, with markets rising steadily, falling more suddenly, and overshooting in both directions as they go. It is a wasteful and expensive process, but it works. Paraphrasing Winston Churchill on democracy, a free capital market is the worst way to allocate capital — apart from all the others ever tried.

All that said, we should not be too relaxed about this equity market sell-off. It is unusual for markets to drop this quickly and violently from an all-time high. This 10 per cent fall took only nine trading days; London’s Longview Economics reports that the S&P has never fallen so far so fast from a record high.

The violence of the move on the basis of still skimpy evidence — a pick-up in wage inflation in a data series that is notoriously noisy and prone to revision — does suggest something strange is afoot. That raises questions about the machinery. Are market structures still in good working order after years in which volatility was suppressed?

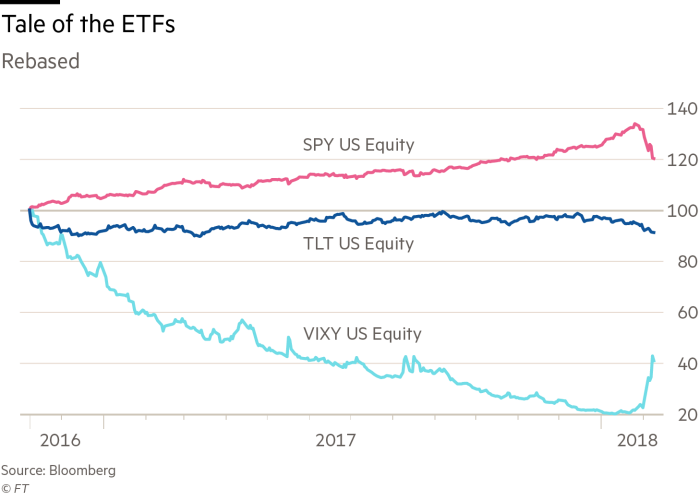

The rise of passive index funds, and particularly exchange traded funds, means entering and exiting the market is now a matter of “top-down” decisions, driven by economic factors, rather than an attempt to find stocks that are too cheap. For many investors, the last year has been the story illustrated in the chart, acted out through ETFs known by their ticker symbols — a sudden fall for SPY (chasing the S&P 500 index) and a rise for VIXY (mapping the Vix volatility index), as TLT (tracking long Treasury bonds) continues a long drawn-out decline.

Combine ETFs with online technology and retail investors can enter and exit markets en masse in a way not possible in the past. Occasionally, the mechanics of the exchange-traded securities themselves can lead the market down.

That is what happened on Monday when various funds designed to move in the opposite direction to the Vix volatility index started to dive as volatility spiked upwards. That sparked a brief and terrifying freefall in markets.

Does this mean that the ETF machinery was itself at fault and should be reined in by law? On balance it does not, but some changes do need to be made.

First, and critically, it is worth bearing in mind that the exchange-traded notes that came to grief were not big enough to bring the entire market into a systemic crisis. They were worth less than $5bn between them, so it is alarming that they caused so much damage, but they were not systemically important.

Also, we cannot credit all of this week’s ugliness to Monday’s volatility spike — as of Friday lunchtime, the market is at a fresh low for the week.

Next, note that these were exchange-traded products, but not ETFs as such. They have at least two critical differences from a normal ETF. First, they do not hold an underlying basket of securities, but instead hold a note underwritten by a bank that will move in line with its strategy each day. That introduces credit risk (the chance that the bank might fail) on top of the risk that the strategy falls. Second, they do not track an index, as they reset each day. They mirror the move each day in the index, making them far more volatile.

It is hard to see why such products should be available to retail investors. The prospectuses were clear about the risk of losing all your money in them, but after 2017, when these funds tripled their investors’ money, it was inevitable that they should prove popular. Such instruments should be for consenting adults only.

Beyond that there is an issue of truth in labelling. BlackRock, one of the three big ETF providers (with State Street and Vanguard), argues that instruments based on notes and involving betting on indices to go down should be clearly labelled as something different from ETFs — a stance in which it differs from others in the industry.

Did other ETFs contribute to the inferno of selling? If anything, they did the opposite. State Street points out that there was trading volume of $85.7bn in ETFs tracking the S&P 500 on Monday — but most of this saw buyers and sellers cancel each other out. In total, the net amount of ETF shares that needed to be redeemed was only $5.9bn.

In other words, traders expressing their view about different asset classes traded $85bn, but the amount of shares in the companies of the S&P 500 that the managers of the funds underlying the ETF needed to sell as a result of all this trading activity came to only $5.9bn. They helped to absorb trading activity rather than creating problems.

This correction may not be over yet. But it owes more to the artificially calm conditions that preceded it, than to the structure of the latest instruments that investors use to trade in it. john.authers@ft.com