There are two important measures that point to a downturn for stocks, according to Longview Economics

Donald Trump used a speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, this week to denigrate America's allies in Europe.

It's been a holiday-shortened week for U.S. investors, but it's certainly packed a lot in.

The S&P 500's SPX 2.1% dive on Tuesday, in response to Donald Trump's pledge to place more tariffs on European allies over their resistance to his Greenland ambition, has already been mostly recovered after the U.S. president's pivot.

With that swift rebound, it is tempting to think little has changed.

However, as Chris Watling, global economist and chief market strategist at Longview Economics, suggests, Trump's rhetoric and threats aimed at allies over Greenland mean significant damage has been done to the transatlantic relationship.

In a note published Thursday, Watling says that non-U.S. investors in the West will now be asking themselves two questions: "Do you sit it out for 3 years and hope for a return to the post WWII norms (i.e. a U.S. re-engagement with the post WWII rules-based order by the next President) at the next election; or do you start to trim strategic (i.e. structural) weightings in U.S. assets."

One issue to consider is that this latest rupture comes as many global portfolio managers were already worried about U.S. fiscal profligacy, according to Watling, "which is understandable given the lack of signs of fiscal consolidation and high/rising U.S. government indebtedness."

"Added to that, and given the unpredictability of this current U.S. Administration, the risk of a cut of your U.S. holdings/assets being taken from portfolios (in a form of tax, a la the [Trump-allied Fed governor Stephen] Miran proposed 'Mar a Lago' plan) must also be at the back of investors' minds," says Watling.

In other words, it may be feared that property rights, in America, are no longer sacrosanct.

However, Watling thinks that, regardless of how much emphasis foreign investors place on Trump's unpredictability, the case for a U.S. secular equity bear market, starting at some point in the few years ahead, is already building.

He highlights a couple of factors that point to this.

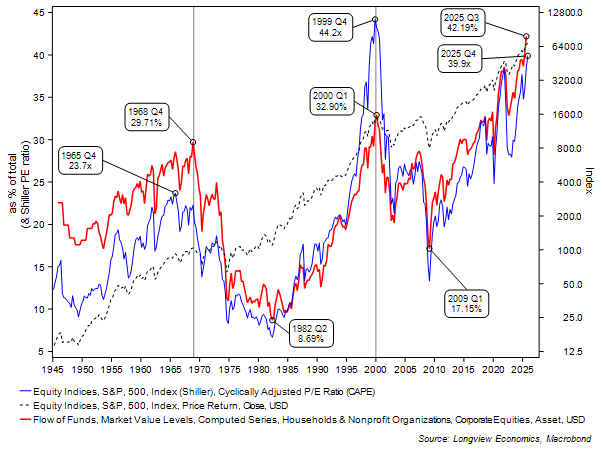

First is valuations, a bad guide for timing a market in the short term, but important in the medium and longer terms. On the latest data, the U.S. stock market is trading on a Shiller CAPE ratio of 39.9, which is the second highest reading on record, he notes. ("CAPE" stands for cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings and is a ratio used to gauge whether a stock, or group of stocks, is undervalued or overvalued by comparing its current market price to its inflation-adjusted historical earnings record.)

Second is elevated levels of stock ownership. Equities account for 42.2% of total U.S. household financial assets, which is the highest proportion ever, according to Watling. Also at a record high: equities as a share of defined-benefit pension assets.

Watling presents the following chart, which suggests previous U.S. secular bear markets began with a combination of valuation peaks coupled with record-high equity ownership. These peaked in 1968 and 1999, and U.S. secular equity bear markets followed in the 1970s and noughties, he notes.

Source: Longview Economics

Watling says that his firm, Longview, remains "tactically and strategically overweight U.S. equities (for now), but cognizant of these causes for concern brewing in the background." He adds: "The case for starting to diversify away from the U.S. is building."